Clinical

Tackling prescribed medicine dependence and withdrawal

In Clinical

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Community pharmacists need to be part of the solution for the millions of people across the UK grappling with prescription drug dependence and withdrawal

A quarter of adults in England take one or more prescription medicine(s) that might cause dependence, withdrawal symptoms or both, according to a new report, Dependence and Withdrawal Associated With Some Prescribed Medicines: An Evidence Review, from Public Health England (PHE).1

Brendon Jiang, RPS English Pharmacy Board member and NICE medicines and prescribing associate, describes it as a landmark document.

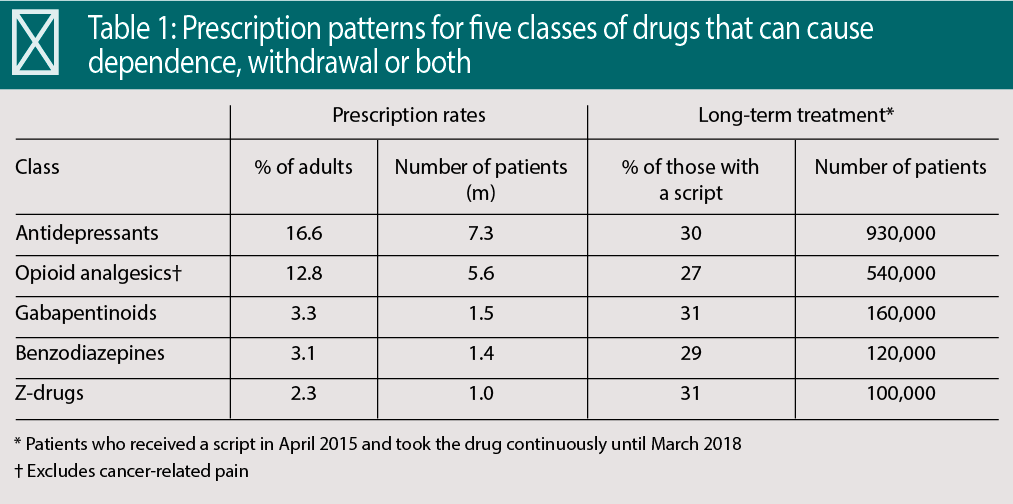

PHE estimates that in 2017-18, 11.5 million adults in England (26 per cent of adults) received one or more prescriptions for anti-depressants, opioid analgesics for chronic non-cancer pain, gabapentin and pregabalin (gabapentinoids), benzo-diazepines and z-drugs such as zopiclone and zolpidem (see Table 1).

“These drugs are vitally important when prescribed properly for the health and well-being of many patients,” says Rosanna O’Connor, director of drugs, alcohol, tobacco and justice at PHE.

“We need to address the problems posed by dependence and withdrawal but care needs to be taken not to inapprop-riately limit the use of these medicines as this could cause patients harm and may lead some people to seek medicines from illicit or less-regulated sources.”

A comprehensive literature review and an open call for evidence from patients has led PHE to conclude that benzodiazepines, z-drugs, opioid analgesics and gaba-pentinoids are associated with a risk of dependence and withdrawal.

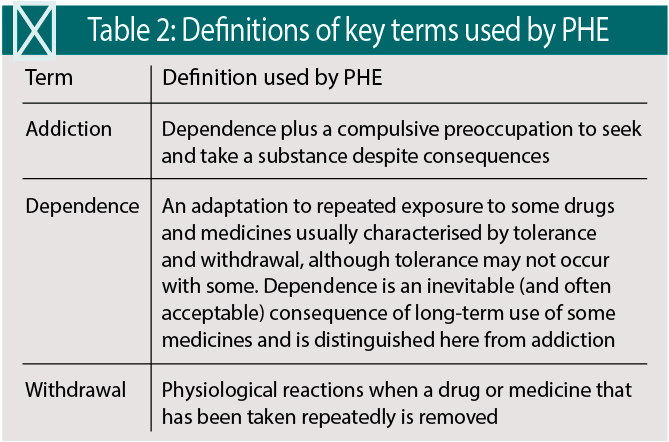

Antidepressants are associated with withdrawal symptoms, such as insomnia, depression, suicidal ideation and physical changes. Patients may mistake the problems they experience stopping treatment for addiction. “It is crucially important to understand the difference between the terms: addiction, dependence, tolerance and withdrawal,” Jiang adds (see Table 2).

Polypharmacy and long-term use

To complicate matters further, PHE found that polypharmacy and long-term use were common. About a fifth of patients (19.1 per cent) were taking two of the five classes of drugs, most commonly antidepressants and opioids (9.3 per cent of the total, some 513,000 people). One in 20 (5.2 per cent) received three classes, most commonly anti-depressants, gabapentinoids and opioids (2.8 per cent of the total, about 157,000 people).

Almost one in 100 (0.8 per cent) and one in 1,000 (0.1 per cent) took four and all five drug classes respectively. This means some 48,000 people in England take four or all five classes. The impact of polypharmacy on the potential for dependence and withdrawal is just one of several areas that urgently need further research. About three in 10 of those prescribed one of the classes received the drugs long-term (see Table 1).

Between 2015-16 and 2017-18, for example, prescribing for antidepressants increased from 15.8 to 16.6 per cent of adults and from 2.9 to 3.3 per cent for gabapentinoids. Prescriptions for the other groups showed small decreases.

Despite the well-publicised concerns over at least some of these drugs, PHE identified “large variations” in prescribing across clinical commissioning groups, which demographics and deprivation only partly explain. In general, rates of prescribing were 1.5 times higher among women than men and increased with age.

For all five classes, the proportion of patients who had at least a year of prescriptions increased among people from more deprived backgrounds. That may be justified for antidepressants, given the psychological devastation often wrought by poverty, but it is not in line with guidelines for the other drugs.

“The review makes a number of recommendations related to reducing variations in practice and it is now for the NHS to take these and other activity forward, including examining the data and supporting adherence to guidance,” O’Connor says.

Lack of information

Patients told PHE they felt there was a lack of information about medication risks and that doctors did not acknowledge or recognise withdrawal symptoms. Patients also felt that they were not offered non-medicinal options and were unable to access effective management and NHS support services.

In addition, patients felt that their treatment was not reviewed sufficiently. “Patients should meet with their GP to review their prescriptions at least annually but preferably three- or six-monthly,” O’Connor advises. “It needs to be a clinical decision, tailored to the patient, their condition and history. Some may need more frequent reviews.”

Pharmacists should encourage people with concerns about dependence and withdrawal to seek professional help. “Patients with concerns about their medicines should not stop taking them, but should speak to a healthcare professional. “We must treat the person behind the prescription and discuss these problems professionally and without judgement,” Jiang says.

Language matters and emphasises the value of a consistent message from healthcare professionals, he says. “No patient actively seeks treatment with the aim of pharmacological dependence or withdrawal. We must shift the narrative from misuse, abuse or addiction, whereby patients risk feeling blamed or victimised, to a factual discussion about the lack of evidence, their awareness of the risks, their perceptions of benefit and what truly matters to them,” he says.

“This does not need to be a sit-down, in-depth consultation. Earlier interventions can be more effective and there is power in consistent messages repeated from all clinicians involved in the care pathway.”

Avoiding withdrawal symptoms means slowly tapering the dose but in some cases the formulations may not be available. “Pharmacists can use their specialist knowledge of pharmaceutics and pharmacokinetics to recommend alternatives,” Jiang says. “An alternative with a longer half-life reduces the dosing interval and onset of withdrawal symptoms.

“Pharmacists can also use their professional judgement, in conjunction with the available evidence to recommend a course of action appropriate to the patient if no licensed form exists.”

Against this background, PHE recommends increasing the availability and use of data on the prescribing of medicines that can cause dependence or withdrawal. This, it argues, would support greater transparency and accountability as well as helping ensure that practice is consistent and in line with guidance. In addition, PHE has called for enhanced clinical guidance and ensuring that healthcare professionals follow the guidelines.

PHE has also suggested improving information for patients and carers on prescribed medicines and other treatments, enhancing informed choice and shared decision-making, and transforming the available support for patients experiencing dependence or withdrawal. Finally, PHE calls for further research on the prevention and treatment of dependence and withdrawal associated with prescribed medicines.

The report notes that there isn’t enough evidence to draw robust conclusions about best practice. Nevertheless, current services offer various combinations of primary care involvement, a helpline, counselling, support groups and individualised plans. And it seems community pharmacists have an important role – one that could expand as recognition of the problems posed by dependence and withdrawal rises among patients and professionals.

No patient actively seeks treatment with the aim of pharmacological dependence

Roles for community pharmacists

“Community pharmacists already practise in ways that can reduce dependence. They clinically assess prescriptions and query or intervene with both patients and prescribers if necessary,” Jiang says. “They counsel patients when initiating new therapies, outlining the expected duration of treatment, safe use, risks, potential harms and requirement for review.

“There need not be a drastic change in practice, but more can be done to support these patients,” he believes.

The continuity of care offered by community pharmacists may be especially helpful when tackling sensitive, contentious issues such as dependence and withdrawal. “Pharmacists and their teams get to know their patients, review any use that strays beyond expected guidelines, and monitor for

and identify signs of misuse or dependency,” Jiang says. “This is the responsibility of the entire team – from healthcare assistants through to dispensers, technicians and pharmacists. Their knowledge of the community and the relationships and trust built over time can facilitate having what can be challenging conversations.”

In addition, community pharmacists can signpost patients to local services. “Apart from referring to the GP, is there a helpline, talking therapy service, cognitive behavioural therapist, support group, specialist support service, community pain team, social prescriber locally, and what is the referral pathway?

Strategically, the PHE report advises that CCGs work with sustainability and transformation partnerships and integrated care systems. The report makes several recommendations about how community pharmacists and NHS structures can help to address the issues in the report.

“This includes improving training provided to primary care services, clinical and community pharmacists. GPs also need to develop their knowledge of, and competence to identify, assess and respond to dependence or withdrawal associated with some medicines and the support needs of people experiencing problems,” O’Connor remarks.

“PrescQIPP audit tools have also been made available to support primary care practices and community pharmacists review and tackle high-dose opioid prescribing. The NHS now needs to take the agenda forward.”

It won’t be a moment too soon. The PHE report clearly and unambiguously lays out the scale of the problem and what the NHS can and needs to do. There is no longer any excuse for equivocation.

Reference

Dependence and withdrawal associated with some prescribed medicines: an evidence review.